Feb 2025

Feb 2025

Silver Hallmarks - Identifying Silver Marks

Silver hallmarks have been used in the UK for hundreds of years. These tiny stamped symbols reveal a lot about an item’s history, quality, and authenticity, including where it was assayed, who the manufacturer was, and the year it was hallmarked.

Although silver hallmarks aren’t typically used in the world of bullion, understanding them can help you verify the authenticity and value of antique silver or family heirlooms. In this guide, we’ll share what you need to know about silver hallmarks and how to read them.

What are silver hallmarks?

Silver hallmarks are small stamps that verify the authenticity, origin, and purity of a silver item. In the UK, hallmarking has been a legal requirement for centuries, serving as a form of consumer protection that helps buyers trust in the metal content of their silver. These marks are applied by official assay offices and serve as a guarantee of quality, similar to a certification seal.

What do silver hallmarks mean?

Each silver hallmark has its own specific meaning. For example, one of the most recognizable symbols in British hallmarking is the lion passant, which has been used to symbolise sterling silver (92.5% pure silver) since the 16th century.

On the other hand, a Britannia figure was used between 1697 to 1720 to signify the increased purity standard of 95.83%, known as Britannia silver.

The four main types of silver hallmarks are the:

- Maker’s mark: This identifies the silversmith or company that produced the piece.

- Assay office mark: This shows where the item was tested and hallmarked (e.g. London, Sheffield, Birmingham, or Edinburgh).

- Fineness mark: This indicates the purity of the silver, usually represented as a number (e.g. 925 for sterling silver).

- Date letter: This is a letter assigned to a specific year, helping determine the item’s age.

Between 1784 and 1890, when tax was placed on gold and silver, a duty mark was also used. This mark featured a profile of the reigning monarch of the time and indicated that the tax had been paid.

Learn More: The Britannia Coin - All You Need to Know

History of hallmarking silver

Silver hallmarking in the UK dates back more than 700 years, making it one of the oldest forms of consumer protection. The story begins in 1300, when King Edward I introduced a new law that required all silver to meet the sterling standard – meaning it had to be at least 92.5% pure. To enforce this, a leopard’s head mark was stamped onto all sterling silver items – a symbol still used today to identify pieces tested at the London Assay Office.

Originally, all silver items were marked at the Goldsmiths’ Hall in London, however other British assay offices were opened over time. Edinburgh has been hallmarking silver since the 15th century, and Birmingham and Sheffield opened assay offices in 1773 under Act of Parliament. In Dublin, an assay office has been operating since the 17th century.

Each city developed its own unique assay mark:

- London assay office: A leopard’s head

- Edinburgh assay office: A three-turreted castle, later featuring a lion rampant

- Sheffield assay office: A crown, replaced by a rosette in 1974

- Birmingham assay office: An anchor

- Dublin assay office: A crowned harp, with the figure of Hibernia added in 1731.

The practice of hallmarking in the UK makes British and Irish silver some of the most traceable in the world.

Continue Reading: Giving Silver as a Gift

Regional hallmarking centres

The UK was once home to several regional hallmarking centres, each with their own mark. Many of these have since closed, making their hallmarks rare and highly sought-after by collectors.

Some regional assay offices, like Norwich, stopped hallmarking silver as early as 1701, while others, like Glasgow and Chester, continued until the 1960s. Collectors often seek out silver from these defunct offices because they have additional historical value. If you find an old silver piece with one of these marks, you might be holding a piece of history.

The below table shows some of the most notable regional assay offices that are now closed, and their hallmarks:

ASSAY OFFICE LOCATION | YEAR OF CLOSING | HALLMARK |

Chester | 1962 | Three wheat sheaves and a sword |

Exeter | 1883 | Crowned X or a three-turreted castle |

Glasgow | 1964 | Tree, bird, bell, and fish |

Newcastle upon Tyne | 1884 | Three separated turrets |

Norwich | 1701 | Crowned lion passant and crowned rosette |

York | 1856 | Half leopard’s head, half fleur-de-lis, later five lions passant on a cross |

Scottish and Irish provincial silver

In Scotland and Ireland, many silversmiths chose to not send their work to major assay offices like Edinburgh, Glasgow, or Dublin for official hallmarking. Instead, they stamped their own silver with unique maker’s marks, town marks, or other symbols. This was often due to practical concerns, since traveling to an assay office could be time-consuming and sometimes risky.

Because of this, Scottish and Irish provincial silver is rare and highly collectible. Many silversmiths in Cork, Limerick, and other Irish towns simply marked their work with the word ‘Sterling’ and their initials instead of using a full set of hallmarks.

In Scotland, more than 30 different towns had local silversmiths (known as hammermen), each using their own distinctive marks. This led to a huge variety of symbols and stamps for Scottish provincial silver. Specialist publications exist to help locate and identify these unique hallmarks.

How to read silver hallmarks

Let’s take a look at how to read silver hallmarks, and examples of the most common hallmarks found in British silver.

Locating the hallmark

Naturally, the first step in reading a silver hallmark is knowing where to look. Hallmark locations can vary depending on the item. For example:

- Flatware, like a silver plate, is usually hallmarked on the back, near the handle or flat edge

- Hollowware, like bowls or teapots, is often stamped on the base, lid, or near the rim

- Jewellery hallmarks are usually found on clasps, inner bands (for rings), or the backs of pendants.

Tip: If the hallmark is hard to read, try breathing on it – the condensation can help bring out the details.

From left to right, these hallmarks demonstrate a maker’s mark, the lion passant, the London town mark, the London 1935 date letter, and a Jubilee mark celebrating George V’s Silver Jubilee in 1934/35. (IMAGE REFERENCE)

The standard mark

The standard mark is one of the most important hallmarks as it confirms an item is made from genuine silver. For most silver items, you’ll find the lion passant mark which indicates sterling silver. This mark has been used for centuries to demonstrate the quality of silver items.

There are two versions of the lion passant mark:

- The original version, known as the lion passant guardant, shows the lion’s head facing forward.

- The ‘modern’ version, updated in 1822, features the lion’s head facing to the left.

Besides the lion passant, you might find items marked with the figure of Britannia, meaning an item is made from 95.83% pure silver. The Britannia silver standard was introduced in 1696 in an effort to combat the amount of coin silver being melted down and used to make other items.

In 1720, the purity standard dropped back to sterling silver so the Britannia mark was no longer used on most silver items. However, it can still be seen today on special pieces made to the higher 95.8% purity standard.

Image 1: The original lion passant guardant design, Image 2: The ‘modern’ lion passant design (IMAGE)

Image 3: The Britannia standard (95.8% purity) [left] (IMAGE)

The town mark

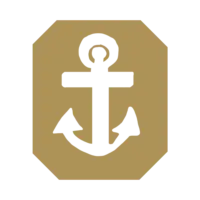

The town mark identifies where a silver item was tested for purity. Every assay office has its own unique mark. For example, the town mark in London is the leopard's head while in Birmingham it’s an anchor.

You can see a list of the most popular town marks earlier in this article.

Image 1: The London town mark, Image 2: The Birmingham town mark (IMAGES)

The date letter (year of assay)

The date letter shows when a piece was assayed, or tested for purity. It also helps identify the touch warden, or person responsible for checking the silver’s purity that year. This hallmark is no longer compulsory as of 1999, however it can serve as a valuable tool for dating silver – especially antiques.

Previously, the date letter changed every year with a new one introduced each January. Once the complete alphabet was used up, after 26 years, a new cycle would begin with a different lettering or shield design. This system made it easy to date silver items, but sometimes there were small changes and exceptions that created anomalies.

While the date letter was generally meant to represent a single year, it wasn’t until 1975 that all assay offices began changing their letters on January 1st each year. Before that, each office changed their letters at different times of year, which is why you can sometimes see silver from certain years labelled with a two-year range.

To read date marks, you’ll need a pocket hallmark guide. Alternatively, online guides exist to help you understand date marks better.

Image 1: A date letter from 1915 | Image 2: A date letter from another cycle in 1935

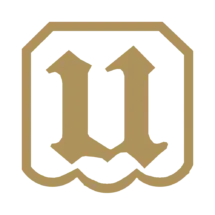

The maker’s mark

The maker’s mark shows who made the silver item – more specifically, the factory it was made in. Unlike other marks, the maker’s mark doesn’t identify the individual craftsman but the company or workshop responsible for making the piece.

Since 1739, the maker’s mark has consisted of the maker or company’s initials. Before that, it included the first two letters of the maker's last name and sometimes objectives or devices. When you have the date mark, it’s easier to find the maker’s mark because you can find out which period the maker was active in.

If you’re interested in learning more about different maker’s marks, there are helpful publications and online guides. For example, Sir Charles Jackson’s book, English Goldsmiths and their Marks is the most authoritative book on the matter, and this online reference can serve as a great tool for identifying maker’s marks.

Image 1: A maker’s mark stamped as a cameo (raised above the background) || Image 2: A maker’s mark stamped as an intaglio (set into the background) (IMAGES)

Keep Reading: Bretton Woods Agreement and the Institutions it Created, Explained

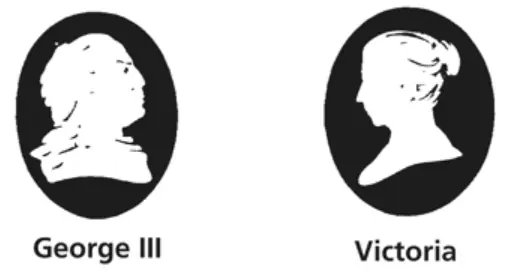

The duty mark

The duty mark appears on many pieces of Georgian and Victorian silver as a symbol that the required tax on precious metals has been paid. Between 1784 and 1890, an excise duty was applied to gold and silver items. Assay offices were responsible for collecting this tax, and the duty mark was stamped on the item to show that it had been paid.

The sovereign’s head was usually used as the duty mark, representing the reigning monarch of the time. For example, the two below hallmarks show duty hallmarks from King George III and Queen Victoria eras.

Image 1: A King George III era duty mark Image 2: A Queen Victoria era duty mark (IMAGES)

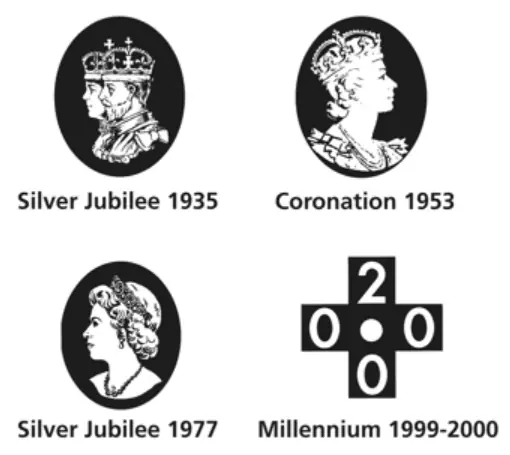

The commemorative mark

Some silver items carry special commemorative marks to celebrate significant events. For example, a head of Queen Elizabeth II facing right was used to commemorate her Golden Jubilee in 2002, and a diamond-shaped mark was issued from July 2011 to October 2912 to celebrate her Diamond Jubilee.

Images: Various examples of commemorative hallmarks (IMAGE)

Summary: Silver hallmarks in the UK

Silver hallmarks are a fascinating piece of British history that can reveal a lot about an item’s quality, authenticity, and age. Whether it’s a silver antique, jewellery, or family heirloom, understanding these hallmarks can help you discover another layer of meaning to silver items and make them all the more precious.

If you’re a silver collector or investor, browse our range of investment-grade silver bullion coins and bars. We stock historic British silver coins like the Britannia and Tudor Beasts series, and high-purity silver bars to safeguard your wealth for generations. Browse our range and start growing your collection today.